The path that some medieval books took across the centuries did not always lead them to the shelves of a library – or, rather, not in their original form. In a period when the transmission of knowledge in books, the administration of power in charters and legal documents, as well as all written private communications had to rely almost exclusively on the use of animal skin, parchment became a precious and expensive material, too useful to be wasted.

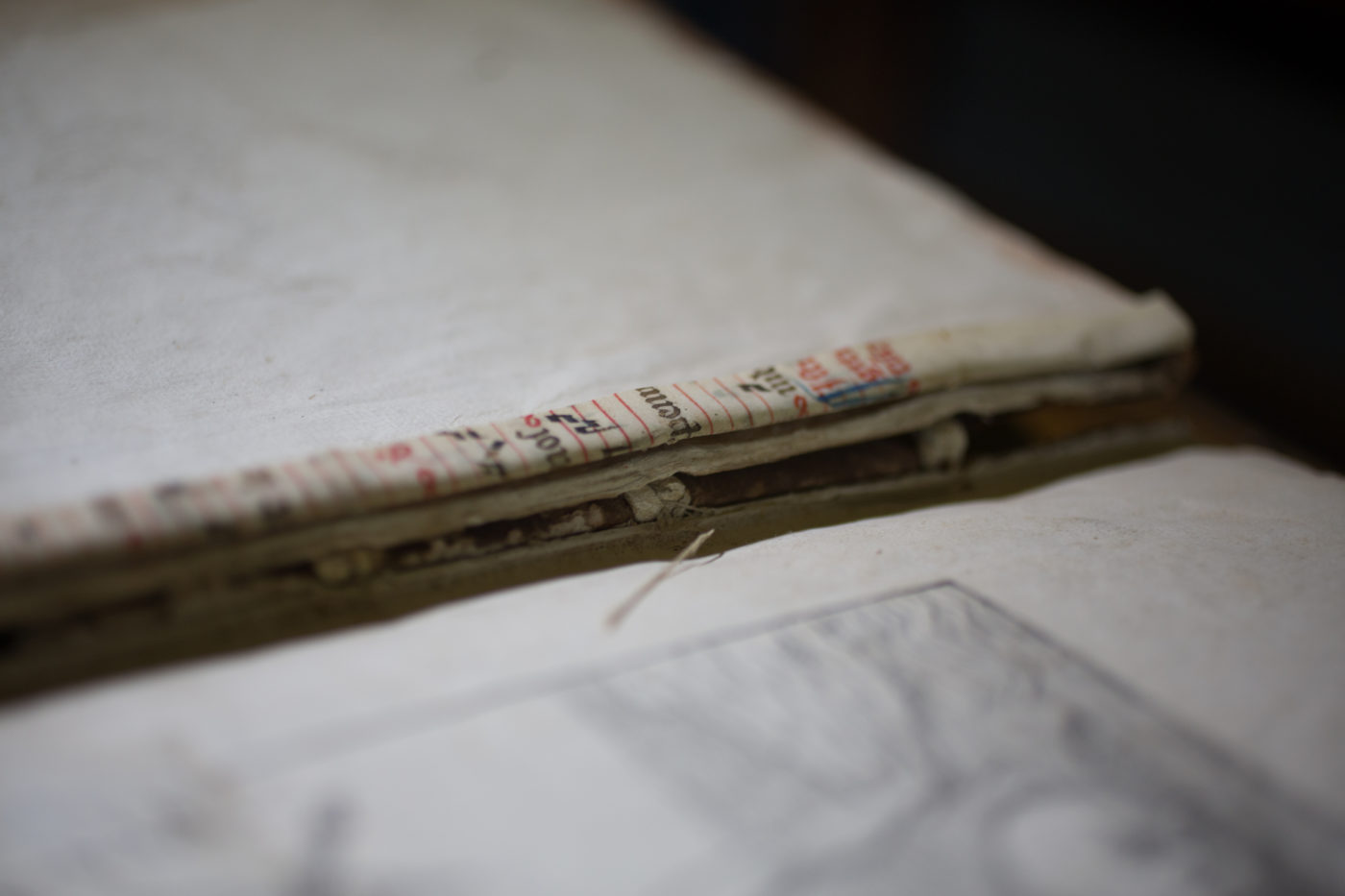

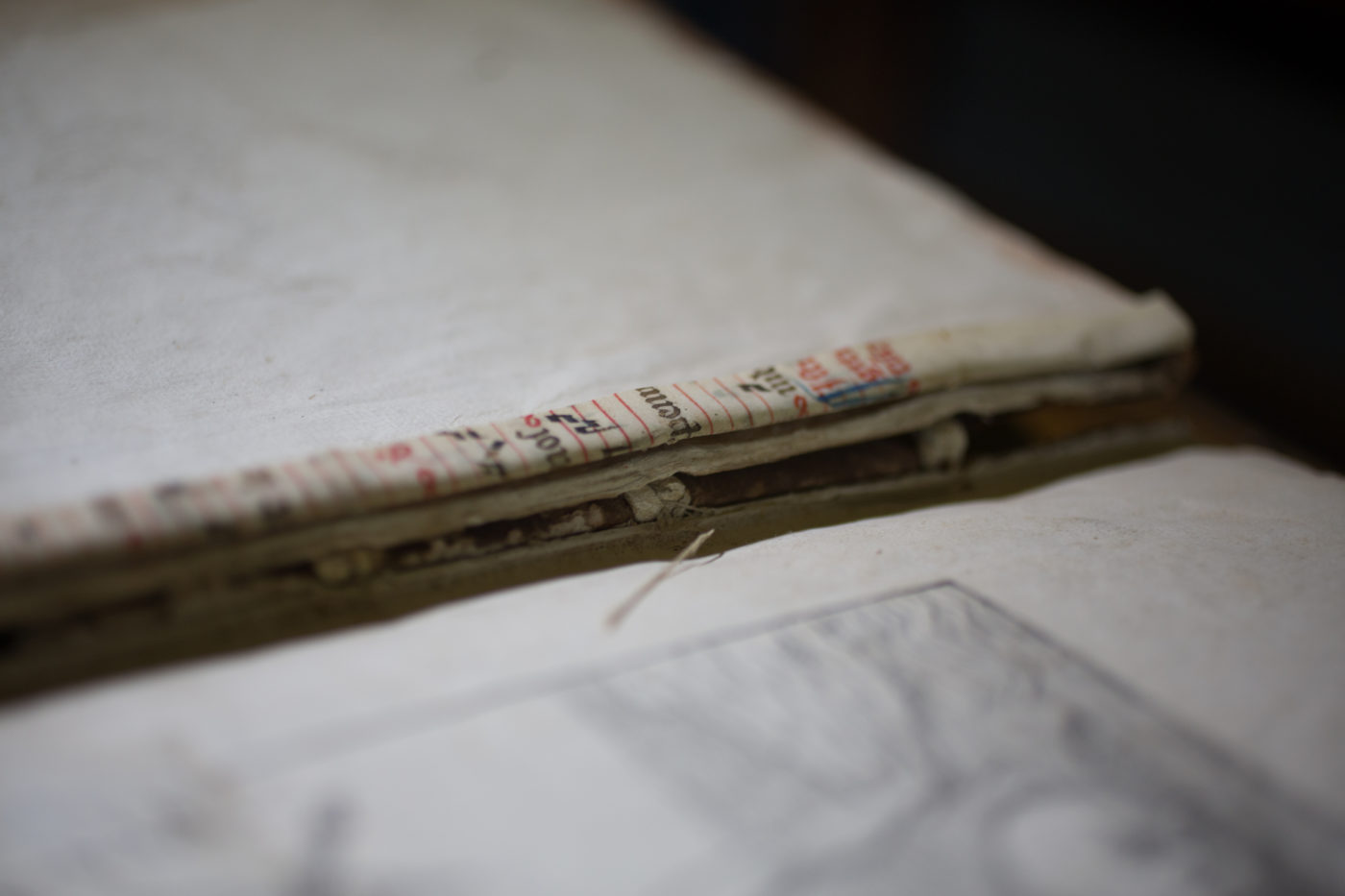

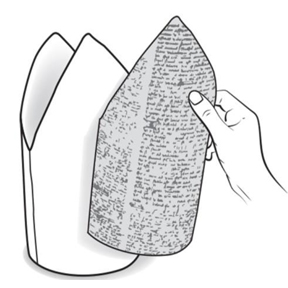

So, when a manuscript fell out of use, or was damaged beyond repair, its constituent parts were dismantled and ‘recycled’ for other purposes. One of the most common uses of such material was for the binding of later printed or manuscript volumes. The wooden boards of old books were reused for a new bindings, and the recycled parchment – from entire leaves, to tiny strips – was employed in various ways inside the binding, the spine, or gatherings, or even as wrappers and covers of new books.

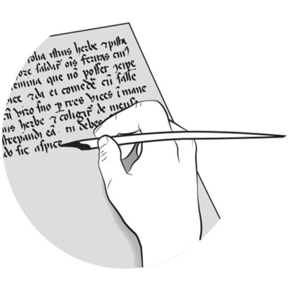

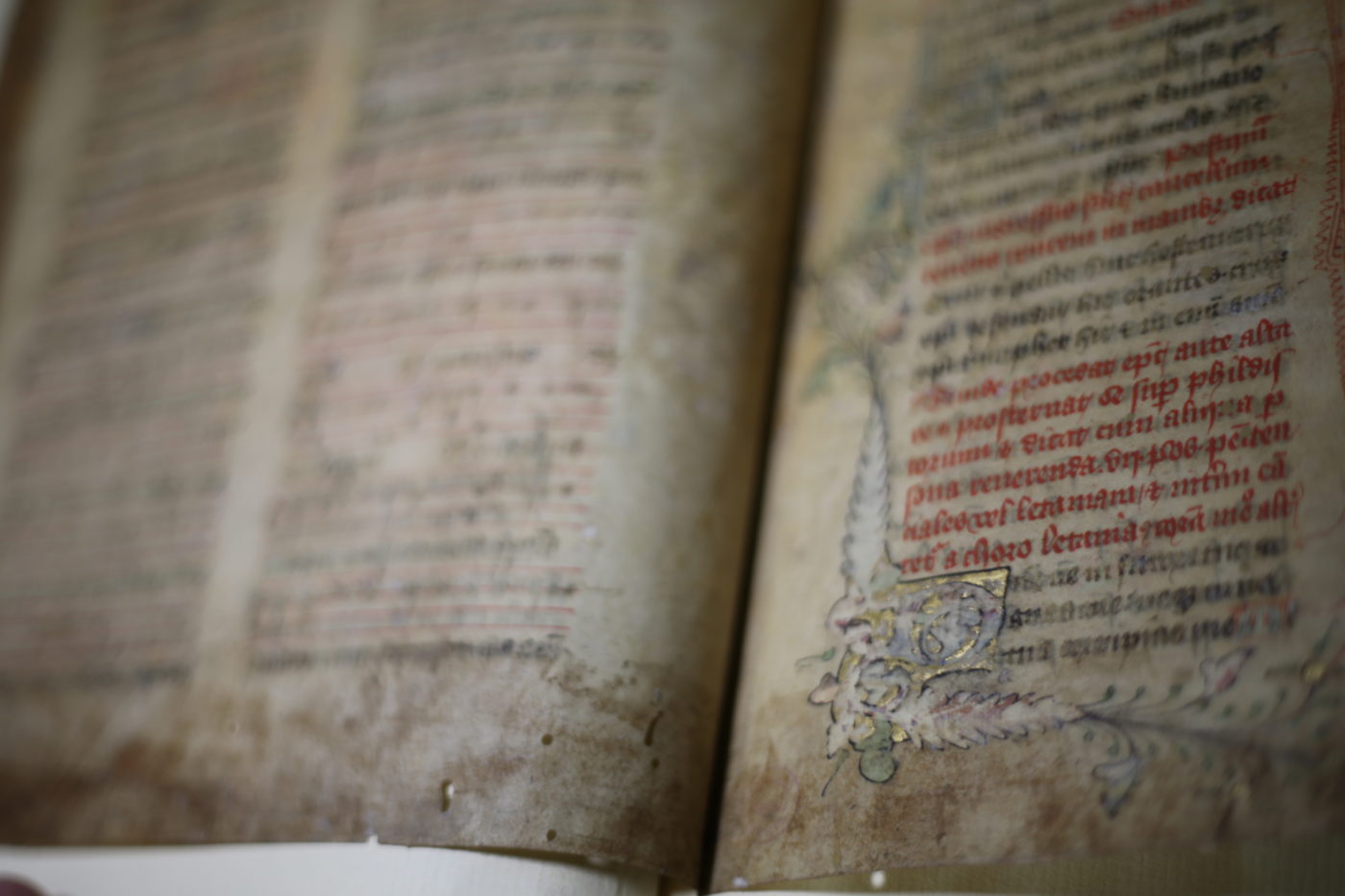

Before the invention of the printing press, and its spread across the western world, all books were made by hand. These hand-made books, or manuscripts, required a whole industry to support their creation: a writing surface had to be made (at first papyrus, then parchment, and only later paper), ink and a writing instrument needed to be prepared, decoration and illumination (gold leaf) planned out. Monastic and professional scribes also needed to be trained in more than one script – all of this without even considering what texts they might be copying.

Before the invention of the printing press, and its spread across the western world, all books were made by hand. These hand-made books, or manuscripts, required a whole industry to support their creation: a writing surface had to be made (at first papyrus, then parchment, and only later paper), ink and a writing instrument needed to be prepared, decoration and illumination (gold leaf) planned out. Monastic and professional scribes also needed to be trained in more than one script – all of this without even considering what texts they might be copying.

The vast majority of manuscripts that survive are, indeed, copies of works passed down from Antiquity or the Middle Ages. These texts were copied over and over again so that the information could be disseminated across large geographical areas and across centuries of time. A few examples survive of medieval authors writing out their own works, yet these are exceptionally rare; usually a text that survives in manuscript form is several steps, and often many centuries, removed from its original author.  The other main type of handwritten book that was common in the middle ages was the more utilitarian type: recipe books, almanacs, records and statutes, and service books for worship.

The other main type of handwritten book that was common in the middle ages was the more utilitarian type: recipe books, almanacs, records and statutes, and service books for worship.

Manuscripts, then, were ‘bespoke’ by their very nature. The maker of the book, or the person paying for it, could decide how large and lavish they wanted their book to be.

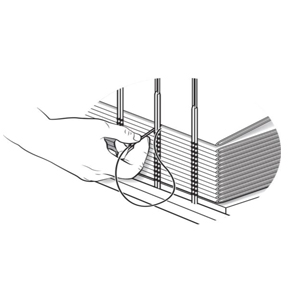

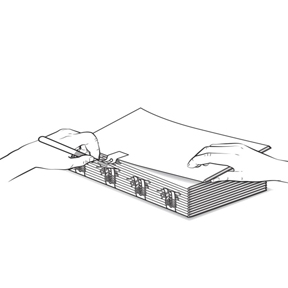

Texts were copied out by scribes onto sheets of parchment and decorated in colour, sometimes illuminated by a specialised artist called limner. The finished leaves were then gathered into quires, which where then sewn onto leather bands forming the structure of the book.

Finally, a binding of wooden boards or other material and a covering layer – sometimes decorated – was applied.

Finally, a binding of wooden boards or other material and a covering layer – sometimes decorated – was applied.

While production of manuscripts, from the preparation of parchment and ink to the binding, in the early Middle Ages took place predominantly ‘in-house’ in monastic copying centres (scriptoria), the late-medieval, ‘commercial’ book often passed through many highly-skilled tradespeoples’ hands before a reader was able to pick up and consult the final product.

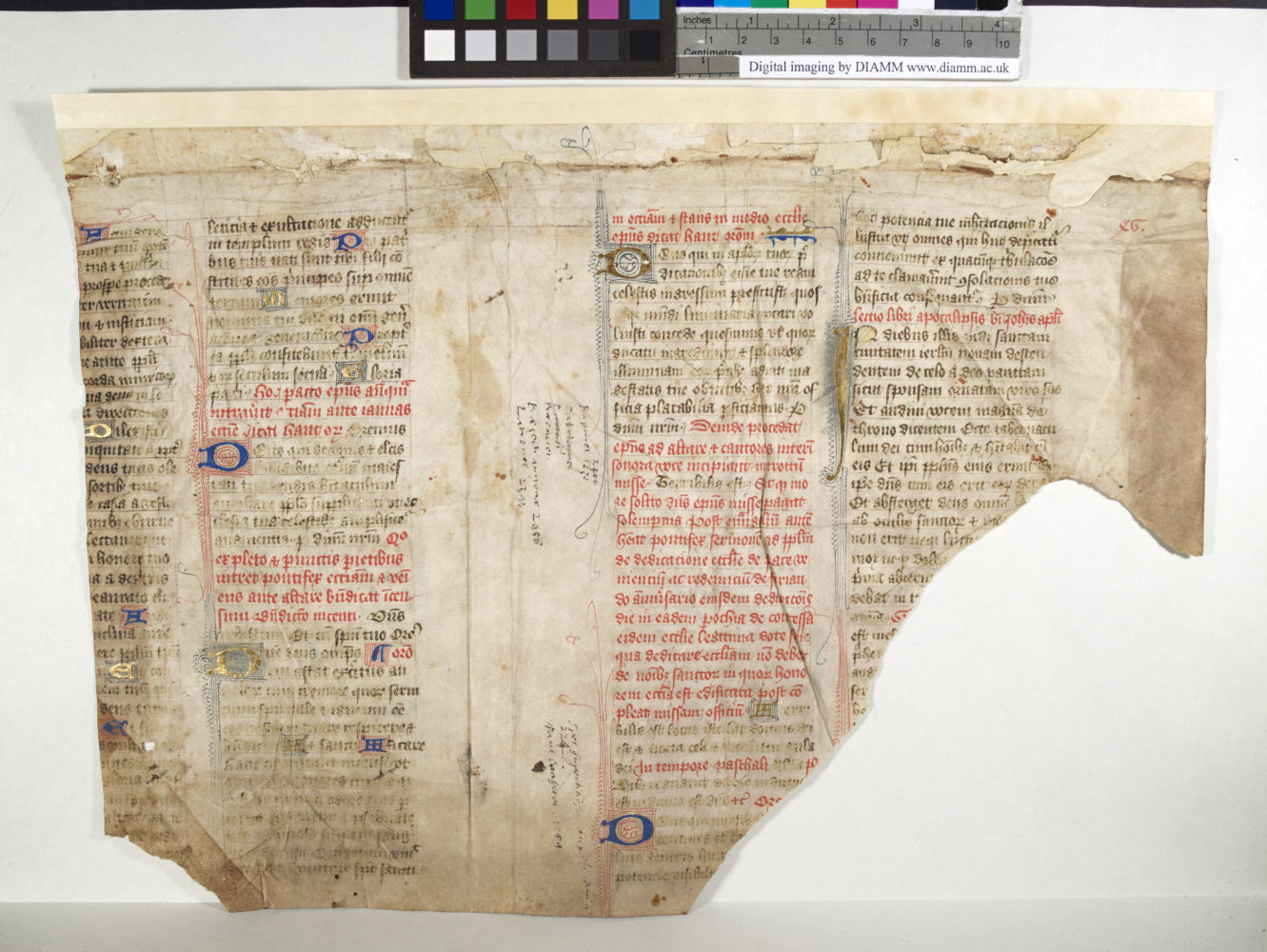

Over the centuries certain texts fell out of use because of changes in philosophical, scientific, or religious thought, and were eventually surpassed by other works. Also, many individual books were used so much by avid readers that over time they simply began to fall apart. Finally, many books created for services and religious worship which included music and instructions for processions were often replaced as modes of worship changed, often as results of religious reforms. Indeed, most of the music that does survive from the Middles Ages is not because it was recopied or printed in later editions, but it survives only in its original manuscript form.

Over the centuries certain texts fell out of use because of changes in philosophical, scientific, or religious thought, and were eventually surpassed by other works. Also, many individual books were used so much by avid readers that over time they simply began to fall apart. Finally, many books created for services and religious worship which included music and instructions for processions were often replaced as modes of worship changed, often as results of religious reforms. Indeed, most of the music that does survive from the Middles Ages is not because it was recopied or printed in later editions, but it survives only in its original manuscript form.

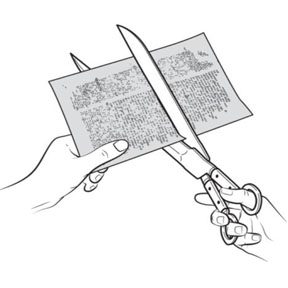

Once these books were considered of no use or were simply beyond repair, their second ‘life’ as fragments began and they were frequently recycled for their constituent parts. Manuscripts were easy to disbind, tear apart, and cut down to get the raw material to a re-workable state. For example, boards could be reused for similar sized books, and paper could be pulped or glued together to make newer and more flexible bindings. Parchment was very useful in providing rigid structure to new bindings, but also stiffening clothes, and making glue.

Once these books were considered of no use or were simply beyond repair, their second ‘life’ as fragments began and they were frequently recycled for their constituent parts. Manuscripts were easy to disbind, tear apart, and cut down to get the raw material to a re-workable state. For example, boards could be reused for similar sized books, and paper could be pulped or glued together to make newer and more flexible bindings. Parchment was very useful in providing rigid structure to new bindings, but also stiffening clothes, and making glue.

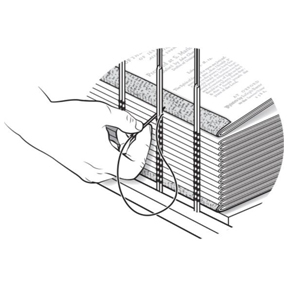

Unfortunately, many texts from Antiquity and the Middle Ages were lost as a result of this process. However, the most common use of these fragments was to act as a support to new binding structures for newer books. Parchment was an ideal medium for stiffening the boards, or covers, of a book, for lining the inside of a book to keep the new leather from wearing off onto the newly printed title page, or to wrap around individual gatherings of pages in the book sewing process.

Unfortunately, many texts from Antiquity and the Middle Ages were lost as a result of this process. However, the most common use of these fragments was to act as a support to new binding structures for newer books. Parchment was an ideal medium for stiffening the boards, or covers, of a book, for lining the inside of a book to keep the new leather from wearing off onto the newly printed title page, or to wrap around individual gatherings of pages in the book sewing process.

Since some of these fragments where used in the binding structures of later books, we are afforded glimpses of individual leaves, or small pieces of leaves, which have survived. Medieval England’s two centres of learning, Oxford and Cambridge, were also the nation’s hub for the circulation of manuscripts and books. In the 15th and 16th centuries, especially during the dissolution of the monasteries and the Reformation, great swathes of manuscripts flooded the book market in these towns. Manuscripts which were no longer of use to the Oxford colleges, such as service books and glossed Bibles, joined the legions of liturgical books from monasteries of the surrounding areas which were to be sold eventually as scrap to binders.

Since some of these fragments where used in the binding structures of later books, we are afforded glimpses of individual leaves, or small pieces of leaves, which have survived. Medieval England’s two centres of learning, Oxford and Cambridge, were also the nation’s hub for the circulation of manuscripts and books. In the 15th and 16th centuries, especially during the dissolution of the monasteries and the Reformation, great swathes of manuscripts flooded the book market in these towns. Manuscripts which were no longer of use to the Oxford colleges, such as service books and glossed Bibles, joined the legions of liturgical books from monasteries of the surrounding areas which were to be sold eventually as scrap to binders.

Suddenly, binders working in Oxford and Cambridge had a great deal of durable and stiff material (i.e. parchment) that they could use to give support to bindings, to make simple wrappers and boards out of, and to even adorn the insides of the books they were binding. It is quite telling that a high percentage of fragments which survive in England are remains of English-made manuscripts. Printed books, too, were subject to fall out of use and reused by binders to support spines, pack boards, or patch up holes. Binders in the 15th-17th centuries would regularly cut down sheets to fit their needs, and in later periods they would also pulp printed sheets to produce thicker ‘card board’.

The transition, or coexistence, of the use of manuscript waste and printed waste illustrates the fact that binders were happy to use anything they could recycle to provide structure to their books. There is arguably some evidence of aesthetic choice in both types of medium, but we also find hints of lost editions of printed works, or lost traditions of manuscripts just by looking underneath the covers.

Fragments are especially fascinating as they often crop up in relatively unusual places, sometimes totally unexpected. A scholar consulting a 16th century book in a library may regularly come across the hints of manuscript waste in the bindings of their books, like a flash from the material past; fragments of lost manuscripts are regularly found between the floor boards of priories and abbeys, or in the voids between walls of old buildings. For a long time, the casual, ephemeral, nature of medieval manuscript fragments led scholars to direct their attention to more complete volumes.

Fragments are especially fascinating as they often crop up in relatively unusual places, sometimes totally unexpected. A scholar consulting a 16th century book in a library may regularly come across the hints of manuscript waste in the bindings of their books, like a flash from the material past; fragments of lost manuscripts are regularly found between the floor boards of priories and abbeys, or in the voids between walls of old buildings. For a long time, the casual, ephemeral, nature of medieval manuscript fragments led scholars to direct their attention to more complete volumes.

As books with fragments survived in collections came up for rebinding, some libraries chose to retain the old fragments as part of a new structure, and sometimes the library didn’t care what happened to the old supports from previous bindings. Binders could sell on these bits of waste to other trades, for example there are records of 18th century Oxford grocers using old leaves of manuscripts to wrap tobacco. There is also evidence of binders of the 19th century extracting manuscript fragments out of old bindings to sell to antiquarians like Philip Bliss, who made a name of himself by trading pots of beer for choice bits of manuscripts from old bindings.

As books with fragments survived in collections came up for rebinding, some libraries chose to retain the old fragments as part of a new structure, and sometimes the library didn’t care what happened to the old supports from previous bindings. Binders could sell on these bits of waste to other trades, for example there are records of 18th century Oxford grocers using old leaves of manuscripts to wrap tobacco. There is also evidence of binders of the 19th century extracting manuscript fragments out of old bindings to sell to antiquarians like Philip Bliss, who made a name of himself by trading pots of beer for choice bits of manuscripts from old bindings.

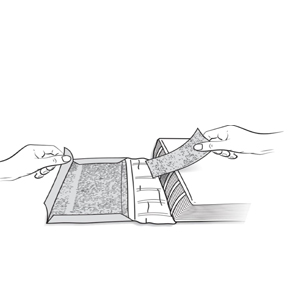

Magdalen’s library collections, like many colleges, went through several rebinding campaigns, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, when fragments where either added or taken out and destroyed. Fragments might have been removed, too, because they were seen as valuable on the second-hand market. However, in the 20th century, the librarians and conservators began preserving these fragments either in situ, or removing them to be placed in guardbooks for safekeeping, denoting the context in which each fragment had survived. In these cases, these pieces of manuscripts are now three or four steps removed from their original purpose. Yet, they still survive today because of the (almost ‘parasitic’) relationship they had with their host volumes in the post-medieval period.

Magdalen’s library collections, like many colleges, went through several rebinding campaigns, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, when fragments where either added or taken out and destroyed. Fragments might have been removed, too, because they were seen as valuable on the second-hand market. However, in the 20th century, the librarians and conservators began preserving these fragments either in situ, or removing them to be placed in guardbooks for safekeeping, denoting the context in which each fragment had survived. In these cases, these pieces of manuscripts are now three or four steps removed from their original purpose. Yet, they still survive today because of the (almost ‘parasitic’) relationship they had with their host volumes in the post-medieval period.

What is really exciting about fragments, more than whole manuscripts, is exactly their incompleteness, their status as scatterings, almost as ruins of a rich and complex past. In them, and each of them in a different, highly individual way we can appreciate more clearly the passage of time, we can imagine the social and cultural context in which they originated, but we can also see their later life as binding material, and finally as objects of study.

Fragments that were once considered as waste, endured through centuries of neglect, and are among the most important sources to preserve the very music that we can now hear and enjoy, some seven hundred years later.

It was not until quite late into the discipline of the study of medieval manuscripts that scholars and antiquarians became interested in fragments themselves. Particularly in the 19th century, with the rise of modern philology, fragments began to be regarded as crucial sources for the reconstruction of particular texts; every available source had to be collected, and its version of a certain text had to be studied in order to access the original, archetypal one. This meant that fragments containing more common texts, like juridical, canonistic, or liturgical ones continued to be largely neglected.

In the course of the last century, however, even those fragments that were previously considered insignificant began to be regarded as precious glimpses into various aspects of medieval life, such as book-making, decoration and, in general, as material objects of a distant past.

In the course of the last century, however, even those fragments that were previously considered insignificant began to be regarded as precious glimpses into various aspects of medieval life, such as book-making, decoration and, in general, as material objects of a distant past.

At Magdalen, most of the fragments in the bindings of manuscripts and early printed books were recovered during the first half of the 20th century, especially under the impulse of medievalist and palaeographer Neil Ker (pictured right) – a Fellow of the College and author of Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries (1969–1992) – during the preparation of his Fragments of medieval manuscripts used as pastedowns in Oxford bindings (1954). The fragments were then placed in specially-designed guardbooks, preserved for future studies.